|

Henry Thoreau in the 21st Century:

Green Simplicity Today

By Gene Sager

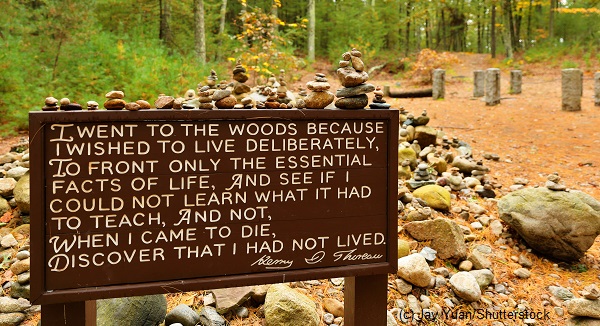

On a pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, I heard a strange but welcome voice which was remarkably pertinent to the social problems we face today. Exhausted by the delayed flights from San Diego to Boston, I barely managed to collect my rental car and drive the 40 miles to the village of Concord. Parking a measured distance from the Walden Pond State Reservation area, I ignored the entrance hours and fee notices and slipped into the empty park at midnight. The only light came from the half moon reflecting on the pond. Mission accomplished, I was able to rest, quieting body and mind near the remnants of Thoreau’s cabin.

In that silence, I heard a voice say “What are you doing?” I figured I had been busted by security, but no one appeared to escort me out. A recalcitrant skeptic of the paranormal, I discounted ghosts, apparitions, and suchlike, but to this day I have no explanation for the conversation I recount here. I asked, “Who are you?” and the voice replied, “I used to live right here by the pond.” I asked him if he was aware of what we have done to the world in the last 200 years. He said, “Yes, I have been watching your progress or lack of it. He added, pointedly, “And you are spinning your wheels. You make an effort to change your situation, but it is to no avail. You try to fix things and you only dig yourself deeper in a hole.”

In defense of present practice, I pointed out that we have problems with plastic but we are recycling it. I said, “To minimize waste, we recycle plastic and use the material to make new plastic products. These in turn get recycled, so we have an economy of circularity.” After a pensive silence, the reply came back: “You created this artificial product that can kill fish and birds and will never become soil; so this is not a natural circularity. It is a circle of complexity. A complex material, redone by another complexity will not reduce your complexity. It is an industrial circle. When you make plastic and when you recycle it, you create more poisons and use more energy or power. You spin this industrial wheel and you go deeper into the hole you make for yourself. Plastics put you in a downward spiral.”

Unable to come back with a worthy response, I said, simply, “So you think the plastics that are not collected for recycle are dangerous clutter and will not become soil; and as for the collected plastics – the recycling process damages and drains our environment. You say the more we spin our industrial wheel, the deeper down we go.” Truth be told, I actually thought he was right. I told him I would think about what he said.

Thoreau then changed the subject to population. He caught me off guard with this: “You have a bovine population problem. You breed and raise too many cattle. Because you crave beef and dairy, you have more complexities. You need tons of grass and hay and grain and water for cattle. You need power to feed, slaughter, refrigerate, and ship. And I don’t even know if beef is good for you.

I stopped him here because I had tried to research these matters and felt helpless to find an answer. My online searches brought up many opinions. The inefficiency of beef idea competed with claims that vegetarians lack protein; and there are studies showing that veganism is quite healthful and better for the earth. I told Thoreau it is difficult to discern which of the myriads of opinions is correct.

For the first time, he laughed. He told me my computer was teaching me to feel helpless. He said, “In my day, computers were newspapers, hearsay, and books. I used to be like you. I almost let them get me confused. But when I came to Walden, I learned to discern for myself with mind and body – brain and stomach.” Thoreau reminded me of his beanfield at Walden, saying “I didn’t have to find or grow feed for the beans, and they served my health better than meat. And I daresay the cattle preferred my eating beans to taking their life to feed myself. A vegetarian diet is much less costly to all and for all. This I suggested to a farmer near Concord. I often spoke with him about living in this world, trying not to tax or spoil it too much. However, the farmer declared that meat is necessary because, he avowed with conviction, ‘You can’t grow strong bones with vegetables.’ With this pronouncement, he urged on his ox whose vegetable-made bones pulled the plow through all obstacles.”

In a desperate attempt to display my knowledge, I pointed out that cows emit methane from both ends. Methane is a problematic gas for the environment, but we have discovered that adding ground seaweed to cattle feed can reduce methane emissions, thus mitigating the problems caused by our cattle population. Here I thought I would impress him. The seaweed solution is cutting edge. But Thoreau was not impressed with my solution. He said seaweed collection, grinding, and shipping is another complex process to solve a complex problem, leading to more entanglements. Again, the vast numbers of cattle make any “solution” a wheel-spinning problem. In his last words to me, he borrowed the phrase “Sweet Sister Simplicity” and urged us to apply her wisdom. “Your smart solutions turn your wheels faster, increasing complexity; and it slows down your progress in solving problems. You can see the irony in ‘faster makes slower.’”

As I collected my backpack and my thoughts, I noticed that the sun had risen and shown through the trees. When I left the park, my exhaustion had melted away. I was invigorated by the knowledge that the rooster was still crowing from Walden, and I was invigorated by the hope that his call will wake us up.

Gene Sager is Professor of Environmental Ethics at Palomar College in San Marcos, California. He is a prolific and thoughtful writer on environmental and philosophical issues, and a frequent contributor to Natural Life.

|