|

Nature Mysticism and Social Action

200 Years After Thoreau

By Gene Sager

We live in a hectic, I would say, frenetic society which overuses Nature and treats it harshly. We are obsessive with our technological devices. Despite great divergence of opinion, or rather because of it, we paradoxically agree that we are severely polarized. Finally, violence abounds, from domestic violence to non-domestic homicides, to ground wars and air strikes abroad. Most of us seem to have resigned ourselves to our condition. I would not call this Henry David Thoreau’s time of “quiet desperation,” but rather one of “desperate tweeting.”

How shall we find the wisdom and grit to change our current situation for the better? American philosopher and author Thoreau is one of the most profound voices I have heard. Here, I apply the most relevant of his insights to our present circumstances. However, I note that, on my reckoning, he made one serious error which we must avoid.

Grounding Ourselves in Nature

First, to re-establish our sanity, we need to re-establish our relation to Nature. Experience in Nature grounds us and brings us to our senses. Thoreau knew so well that attending to Nature is an antidote to frenzy. This, above all, is the value of Nature for us – rather than its usefulness for producing products. In his commencement address at Harvard University in 1837, Thoreau declared, “This curious world we inhabit is more wonderful than it is convenient; more beautiful than it is useful; it is more to be admired and enjoyed than used.” (Walden and Other Writings by Henry David Thoreau, ed. JWKrutch)

The wonder and beauty of Nature, when savored deeply and often, is the core experience of Nature mysticism. With this comes serenity and a powerful sense of the unity of all things. It instills a protective inclination as well. But the poor word “mysticism” has too often been programmed in people’s minds with a link to the esoteric or occult. Such associations are not part of the classic definition and definitely not part of Thoreau’s experience. His Nature mysticism was based on leisurely walks in Nature; no trances and no magical visions. “Simplicity” was his watchword, in housekeeping and in spiritual life.

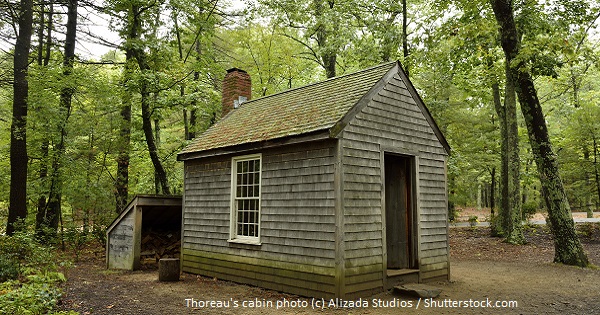

Experience of Nature need not be the experience of wilderness Nature. Many urban areas have a measure of natural environment. Even the Big Apple has a Big Park (Manhattan’s Central Park), including glacier-polished schist boulders. And we need to dispel the myth of Thoreau as the “wild woods hermit.” Even when he was living near Walden Pond, his cabin was about a mile from Concord and he walked into the village most every day.

Social Conscience versus Tranquility

The serenity of his walks was his most coveted experience. But the pangs of his social conscience gradually came to compete with this tranquility. He was saddened by the needless complexity of his neighbors’ lives and by the war of greed (as he saw it) over the border with Mexico; he was angered by the institution of slavery and the Fugitive Slave Law which required his neighbors to report runaway slaves. He could not but voice his opinion and take action to challenge his compatriots. Faced with the two horns of the dilemma – the serenity of Nature mysticism and the turbulence of social action – he strove to attain a balance between them.

We deal with a parallel set of issues today: over-consumption and climate change, US military action in multiple foreign countries, and heated issues concerning immigration and sanctuary. Like Thoreau, we need balance, including an inner balance so as not to complicate our lives with increasing verbal and physical violence.

Thoreau was for many years consistently non-violent in his protests. On several occasions, he called and presided over township meetings to rouse his neighbors. In an act of civil disobedience, he refused to pay his poll taxes and was jailed in Concord. His famous essay “Civil Disobedience” is a brilliant, closely reasoned argument. Based on the clear distinction between morality and legality, it is a guide for effective, non-violent social action and has inspired the likes of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Tolstoy.

The Error to be Avoided

Although in “Civil Disobedience” Thoreau recommends non-violent protest, he does include a passage which warns that in some situations violence may be “unavoidable.” His writings began to take on a more strident tone in later articles like “Slavery in Massachusetts,” which was a harangue of savage indignation.

Then, on May 21, 1856, abolitionist John Brown instigated a violent attack in Kansas, resulting in the murder of five pro-slavery citizens. Thoreau supported Brown wholeheartedly, although many abolitionists withdrew their support from him. Thoreau’s state of mind was, at this time, uncharacteristic. “I walk,” he said, “toward one of our ponds, but what signifies the beauty of Nature when men are base? We walk to see our serenity reflected in them; when we are not serene, we go not to them.” When writing about Brown, he said, “I put a piece of paper and a pencil under my pillow, and when I could not sleep, I wrote in the dark.”

In this crisis situation, Thoreau lost the balance between Nature mysticism and social action. He had said he was a “reluctant crusader,” and his reluctance is understandable. Engagement in social controversy is stressful, confusing, and can throw one off balance – even lead to regrettable words and actions.

Thoreau thought he was facing an “unavoidable” situation in regard to slavery. Following John Brown’s logic, he thought that since slavery was defended by violent forceful means (by the military and police), one is justified in using violent force to counter it. Apparently, he did not realize that if force is used to combat force, then force will be used to combat force to combat force – force to stop force to stop force. The pattern will escalate and continue.

We can learn much from those who have faced troubled times like ours. I hope these thoughts about Thoreau’s reactions will help us find a balance between our sources of serenity and non-violent social action.

Gene C. Sager is Professor of Environmental Ethics at Palomar College in San Marcos, California. He is a prolific and thoughtful writer on environmental and philosophical issues.

|