Ask Natural Life:

Eliminating Plastic From Our Lives

by Wendy Priesnitz

Q: My wife has suggested that our family try to go plastic-free. But the idea of that seems pretty overwhelming. What are the effects of plastic on people and the environment? Is it worth it to make the sacrifices we’d have to make to eliminate plastic from our lives?

A: Plastic is ubiquitous. And that makes it a huge problem for the health of both people and the planet. The main areas of concern are the pollution that occurs during the manufacturing process and in the form of waste when it’s discarded, and the health effects from its use in connection with food.

The International Plastics Task Force, a global network of activists, ecologists, non-profit organizations and waste management experts, says that “plastic has become an environmental problem of global scale.”

Plastics are essentially a byproduct of petroleum refining – and, of course, petroleum is a non-renewable and rapidly declining resource. The components of oil or natural gas are heated in a “cracking” process, yielding hydrocarbon monomers that are then chemically bonded into polymers, which are long-chain molecules. Different combinations of monomers produce polymers with different characteristics. Additionally, various chemicals such as plasticizers, antioxidants, anti-static agents, colorants, flame retardants, heat stabilizers and barrier resins are added to give plastic products their performance properties.

Among the 47 chemical plants ranked highest in carcinogenic emissions by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 35 are involved in plastic production.

In the late 1990s, the Oakland Recycling Association commissioned an analysis of the toxic chemical burden of the plastics industry using data from the EPA, especially the Toxics Release Inventory. In the Report of the Berkeley Plastics Task Force, it said that the plastics industry contributed 14 percent of the national total of toxic releases.

Significant releases of toxic chemicals included trichloroethane, acetone, methylene chloride, methyl ethyl ketone, styrene, toluene, benzene, and 1,1,1 trichloroethane. Other major emissions from plastic production processes include sulfur oxides, nitrous oxides, ethylene oxide, methanol, and other volatile organic compounds.

Dioxins, which are highly toxic even at low doses, are produced when plastics are manufactured or incinerated. While dioxin levels in the environment have been declining for the last 30 years, they break down so slowly that some of the dioxins from past releases will still be in the environment for many years to come.

The Berkeley Plastics Task Force says that although the refining process uses waste minimization methods, air emissions are still high because of inherent difficulties in handling large flows of pressurized gases.

Manufacturing PET resin generates more toxic emissions (nickel, ethylbenzene, ethylene oxide, benzene) than manufacturing glass. Producing a PET bottle generates more than 100 times the toxic emissions to air and water than making the same size bottle out of glass, according to the Berkeley Plastics Task Force.

PVC is another type of plastic that presents notorious environmental problems. Its manufacture involves the use of hazardous raw materials, including the basic building block of plastic, vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), which is explosive, highly toxic and carcinogenic. PVC production facilities have a long history of generating complex and hazardous chlorinated wastes, some of which are inevitably released into the surrounding environment.

Health Issues

People are exposed to these chemicals not only from the manufacturing process, but also by using products made from plastic, by eating food contained in plastic packaging and even by breathing them as they off-gas in the indoor environment.

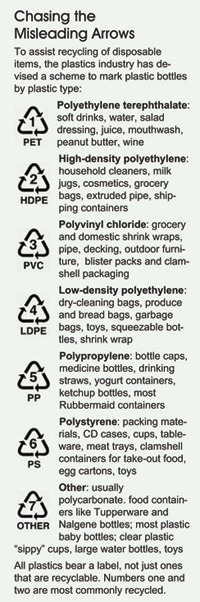

One substance of concern is Bisphenol-A (BPA), an endocrine disruptor that has been widely used in polycarbonate products like food containers, water bottles, baby bottles, eyeglass lenses, nail polish, dental sealants, water pipes and the plastic lining of food cans. (Some plastics bearing the numbers 03 and 07 – see chart above – have been found to leach BPA.) Endocrine disruptors behave like the hormones estrogen and androgen and could wreak havoc on the body’s endocrine system. The National Clearinghouse for Worker Safety and Training reported in its newsletter in 2000 that University of Missouri researchers found that extremely low amounts – 100,000 times smaller than thought – of BPA causes reproductive problems in mice.

In 2008, researchers at the University of Cincinnati announced in the journal Toxicology Letters that when polycarbonate bottles were exposed to boiling water, BPA was released 55 times more rapidly than when exposed to cold water. That finding had huge implications, given the widespread use of this plastic for baby bottles, which are regularly boiled for sterilization purposes.

Researcher Dr. Scott Belcher stresses that it is still unclear what level of BPA is harmful to humans. But he urges consumers to think about how cumulative environmental exposures might harm their health. And children are, of course, more at risk due to their small body size.

In 2006, the Canadian government selected BPA as one of 200 toxic substances deserving of thorough safety assessment; it had not previously been studied by them in depth, having been grandfathered when stricter regulations were passed in the 1980s. As a result, in 2008 it banned the use of BPA plastic in baby bottles. Research is ongoing but some U.S. retailers have stopped selling polycarbonate bottles. A report issued in January, 2010 by the U.S. FDA raised further concerns regarding exposure of fetuses, infants, and young children and suggested that parents limit exposure.

Plasticizers, which are commonly added to PVC as softeners, pose another concern. Also known as phthalates, they make plastics flexible and durable and are used in everything from electrical cables, hoses, gaskets and vinyl sheet flooring to toys, teething rings, and medical equipment. They have also been found in infant shampoos, powders, and such.

Although there is conflicting research, some phthalates are endocrine disruptors. The use of some phthalates in children’s toys is restricted in the European Union and will be in California starting next year. The majority of Americans tested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have metabolites of multiple phthalates in their urine.

A study published in December, 2018 in the JAMA journal Pediatrics found that prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with poor language development in children between 30 and 37 months of age. In this cohort study of 2 independent studies that included a total of 1333 mother-child pairs, exposure to dibutyl phthalate and butyl benzyl phthalates during pregnancy was significantly associated with language delay in preschool-aged children. More research was deemed to be warranted.

In the late 1990s, scientists at the Consumers Union found that some plastic deli wraps use a plasticizer known as DEHA, which has been show to be an endocrine disruptor in rats, and that it could leach from the plastic into fatty foods such as cheese and meat.

A study by Finnish researchers, which was published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2000, showed that plastics found in flooring and indoor wall surfaces may have adverse respiratory effects on children. Many of these materials, which are PVC-based, can emit plasticizers, solvents, and alcohols. The study, involving over 2,500 children, showed that the risks of respiratory symptoms typical of asthma were associated with the presence of plastics. The overall risks of asthma and pneumonia were also increased in those children exposed to plastics than those unexposed. In 2004, a joint Swedish-Danish research team found a very strong link between allergies in children and the phthalates DEHP and BBzP.

Disposal Issues

Plastics are very stable and therefore stay in the environment a long time after they are discarded, especially if they are shielded from direct sunlight by being buried in landfills. Decomposition rates are further decreased in food containers by the antioxidants that are often added to enhance their resistance to attack by acidic contents.

At the same time, the low cost of plastics has enabled the development of disposable products, which has increased the amount of trash. Plastics account for an estimated one-quarter of all waste in landfills. Tens of billions of pounds of plastic are used for packaging designed to be discarded as soon as the package is opened.

Some types of plastic are accepted in municipal recycling programs. But, as the International Plastics Task Force points out, plastics don’t actually recycle. Instead of being reformed back into the original products, they are reprocessed into secondary (and usually non-recyclable) products. This is due to several factors, including structural/ chemical sensitivity, the extremely low cost of virgin plastics, and poor product design. Extended producer responsibility would change that, with manufacturers legally required to ensure socially and environmentally sound product design, which would include biodegradability or producer take-back policies.

While containers are usually made from a single type and color of plastic, which makes them relatively easy to sort for “recycling,” a consumer product like a cellular phone may have many small parts consisting of over a dozen different types and colors of plastics. The resources needed to separate those various components often exceed their value on the secondary products market.

Greenpeace USA released a report in February of 2020 suggesting that many recycling facilities can only accept two types of plastic items – bottles and jugs labeled PET #1 and HDPE #2 (see chart above) – because those are the kinds that have enough market demand and domestic processing capacity. The group surveyed close to 400 material recovery facilities located in the U.S. and found that only those two types of plastic should even be labelled by manufacturers as recyclable. Among the items that are accepted by many municipal recycling programs but not actually recycled (and are instead sent to landfills or incinerators) are plastic tubs, cups, lids, plates, and trays, such as those labelled #3 to #7.

In addition, a significant amount of plastic never even ends up in landfills or recycling programs. Plastic trash has made its way to coastal ecosystems and the ocean, presenting a danger to marine and bird life. Greenpeace says that about ten percent of the 100 million tonnes of plastic produced each year ends up in the sea, notably in a floating “island” in the north Pacific that is twice the size of Texas and swept together by ocean currents. The plastics act as a sort of “chemical sponge,” concentrating many damaging pollutants and transferring them up the food chain.

Solutions

Biodegradable plastics made with plant-based materials have been available for many years but have not replaced traditional mass market plastics. Traditional plastics are not biodegradable because their long polymer molecules are too large and too tightly bonded together to be broken apart and assimilated by organisms that aid decomposition. However, plastics based on plant polymers derived from wheat or corn starch have molecules that are readily attacked and broken down by microbes.

The biotechnology and agricultural industries have tried three main approaches: converting plant sugars into plastic, producing plastic inside microorganisms and growing plastic in corn and other crops.

However, these processes have proven to be just as energy-consuming and chemical-emitting as traditional plastic manufacturing. And so-called biodegradable plastic does not always live up to its name, nor do all municipal programs accept it in either their recycling or composting programs.

Two scientists who work in industry and academia to develop technologies for making biodegradable plastics – Tillman Gerngross from Dartmouth College and Steven Slater with Monsanto subsidiary Cereon Genomics – have decided that the formerly most promising approach of growing plastic in corn plants would consume even more fossil resources than most petrochemical manufacturing routes. They concluded that, “The environmental benefit of growing plastic in plants is overshadowed by unjustifiable increases in energy consumption and gas emissions.” Both Monsanto and Cargill Dow have been considering using biomass to solve that problem.

Recycling programs are, in my opinion, one way for industry to push responsibility for our massive waste plastic problem onto consumers, when it should be producing less plastic. Manufacturers might be encouraged to work harder to clean up their dirty industry if we refuse to buy plastic products and avoid its use as a packaging material. So we encourage you to do what you can to decrease or eliminate plastic from your life.

Avoid The Plastic Menace

- Store foods, especially those with high fat content, in something other than plastic, preferably glass jars or Pyrex-like containers. Note: aluminum foil is not an environmentally perfect option; if you must use it, wash and reuse as many times as possible, then recycle it.

- Avoid microwaving foods in plastic and do not allow plastic wrap to touch food when microwaving.

- When purchasing foods wrapped in plastic, trim off a thin layer where the food comes into contact with the plastic and store the rest of the food in a non-plastic container.

- Buy cheese and meat from a dairy and butcher and ask them not to wrap it in plastic.

- Avoid plastic bags at stores by taking reusable cloth bags.

- Buy foods like peanut butter, as well as laundry soap, shampoo and other products in bulk, using your own containers.

- Avoid canned and take-out food.

- Make your own yogurt at home.

- Buy eggs in paper cartons and return them for reuse or recycling.

- At coffee shops, take your own mug or, if you’re not having it “to go,” ask for a china mug.

- Wash and reuse any plastic containers you feel you must buy.

- Here are more ideas for reducing your use of plastic.

Wendy Priesnitz is the editor of Natural Life Magazine and a journalist with over 40 years of experience. She is also the author of 13 books. Read more about her on her website. This article was first published in Natural Life Magazine in 2008 and has been updated most recently in 2019.

|