Plant a Pollinator Garden for Biodiversity -

Attract Butterflies, Bees, and Hummingbirds

by Robin Eisman

Photo by Claire O. Gudewich |

Some years ago, I planted a small butterfly bush in front of our house just outside Philadelphia. Within a year or two, I regularly counted a dozen or more butterflies at a time, including the swallowtails and cabbage whites that frequent our area, perching like miniature artworks on this now-tall bush with showy flower spikes, some upright, some gracefully drooping. Although butterfly bush is not native to the western hemisphere, I’ve discovered a wealth of native (and other exotic) plants that attract butterflies as well as hummingbirds and bees.

What do butterflies, hummingbirds, and bees have in common? And why would we want to attract them to our gardens, other than for sheer aesthetic pleasure? The large group of animal species known as “pollinators,” which includes various insects, birds, and other wildlife, is unrelated except through their ecological role of pollinating most flowering plants (including trees.) This role is critical to humans because an estimated third of our food supply, as well as some of our fibers and medicines, depends on these pollinators.

We’re aware of the threats to some of these species, such as monarch butterflies. A less-recognized problem is that many other pollinators, including native bees and honeybees (introduced from Europe, Africa and Asia), also suffer from declining populations. Among the factors contributing to these declines are improper use of pesticides, habitat loss or degradation, disease, and competition from non-native species. As pollinator populations decline, so do the plants and trees that require them for pollination – and thus reproduction – and the complex networks of whole ecosystems can be disrupted.

So how can we help out these animals so they can continue to help us? We can make our gardens – large or small, urban, suburban or rural – good sources of food and shelter for pollinators. In return, we can see and literally taste the fruits of their labor, enjoy the pure delight of watching them, and know that we are protecting our local ecosystems.

|

Make your garden pollinator-friendly

Avoid using pesticides, even “natural” ones such as Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt).

Choose old-fashioned varieties of flowers whenever possible, because breeding has caused some modern blooms to lose the fragrance and/or nectar needed to attract and sustain pollinators.

Design your garden so that there is a continuous succession of plants flowering from spring through fall – check for the species or cultivars best suited to your area.

If you decide to use plants that aren’t native to your region, choose ones that don’t spread easily, since these could become invasive.

To provide puddles as a water source for butterflies (and other welcome visitors) without letting them become a mosquito breeding area, either refill containers daily or bury a shallow plant saucer to its rim in a sunny area, fill it with coarse pine bark or stones and fill to overflowing with water. Butterflies can drink from the cracks between the filler but mosquito larvae have a difficult time becoming established.

|

What pollinators need to thrive, like most creatures, are sources of water and food as well as shelter from harsh weather and predators. In many cases, the plants and trees we cultivate and other habitat elements we provide are beneficial to multiple pollinators. Pollinator species and the native plants they’ve evolved with often occur only in certain regions, so a good way to figure out what plants will most effectively attract them to your own garden is to simply observe pollinators in local parks or weedy areas.

Butterflies

General requirements for butterflies are plants for their caterpillars to feed on and large clumps of small, sun-loving flowers to provide nectar for adults. These plants include zinnias, marigolds, tithonia, buddleia, milkweeds, verbenas, and most herbs if they are allowed to go to flower. Keep in mind that the caterpillars of many butterfly species feed on only one or a few plant species (though those plants may feed other species as well,) while some caterpillars feed on many species. Native milkweed, for example, is a food source for monarchs and other butterflies, and is the sole food source for monarch caterpillars. While monarchs have a very restricted food source, eastern tiger swallowtails feed on tulip trees and lilacs, among a number of trees and bushes.

Besides food sources, some patches of long grass for egg-laying, open patches of damp soil or sand for nutrition, and some flat stones in an open, sunny area for basking will provide a welcoming habitat for these gorgeous creatures. Beautiful and elegant as they are, butterflies are known to feed on animal carcasses and dung, which, along with sand, provide essential salts and other nutrients. To provide these, you can create an artificial puddle and “spike” it with mineral-rich sea salt and dung.

Bees

Attracting local bees, or encouraging the ones already in your location, isn’t hard. While honeybees and some bumble bees are social, living in colonies with a queen, most of the several thousand bee species in North America are solitary, meaning that most females build their own small nests. Many bee species prefer to nest in exposed, sandy, well-drained soil in sunny areas, while others prefer piles of branches, untreated lumber with nail or beetle holes, pithy stems, or hollow reeds and bamboo – all of which should be kept dry. Mud with nearby water sources attracts mud-nesting bees, while unshaded, south-facing sandy banks, especially in cold climates, attract bees that nest underground; dry adobe walls and shallow caves attract other species. Bumble bees usually nest in abandoned field mouse nests, found in undisturbed areas such as woodlots, hedgerows, old barns, and brush or compost piles. Hundreds of flowers species attract bees, of course, especially purple and blue ones, but don’t overlook such humble flowers as the dandelion and clover, which thrive and blossom with no work on our part! As for stinging, which only females can do, most bee species aren’t aggressive and generally ignore humans.

Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds, which have been called “the flowers of the air,” are found only in the western hemisphere. Of the 340 known species, only the ruby-throated hummingbird is found regularly east of the Mississippi. Their feeding on flower nectar while hovering is well known, but few people realize that they also eat tiny insects and spiders. In fact, one more reason to avoid pesticides is the possible starvation of hummingbird nestlings if not enough insects are available – and sprayed pesticides can be directly lethal to these birds.

Hummingbirds visit flowers in both sun and shade, and while they are certainly attracted to tubular red flowers, they feed on other types as well – butterfly bush (buddleia) is a magnet for hummingbirds. Besides flowering plants, hummingbirds, like many birds, need shrubs or trees with dense foliage to provide shelter from predators and places for nesting and perching; they also need a source of water. If you use a hummingbird feeder, fill it with sugar-water (not a honey solution, which can support fungi that are fatal to hummingbirds); clean and refill the feeder every three to five days.

What to Plant

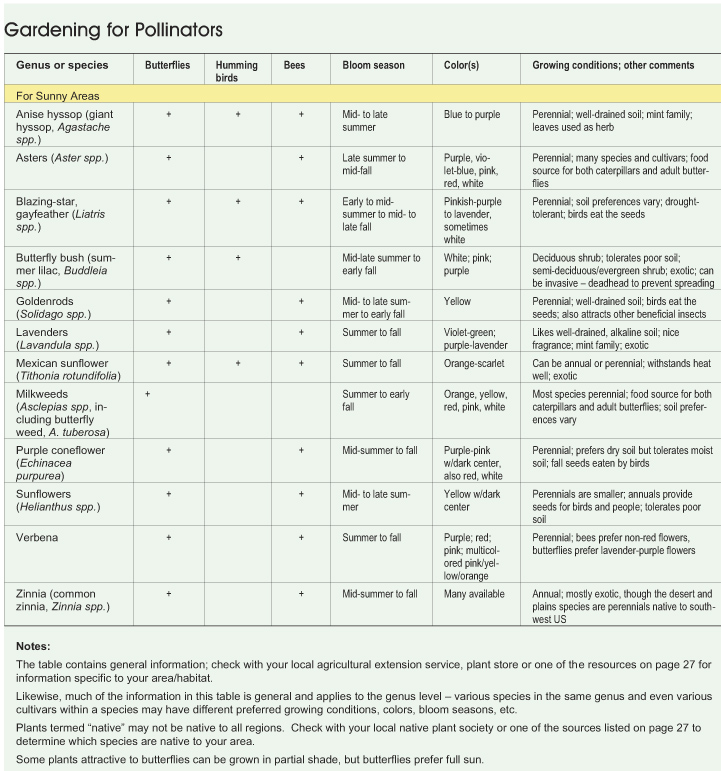

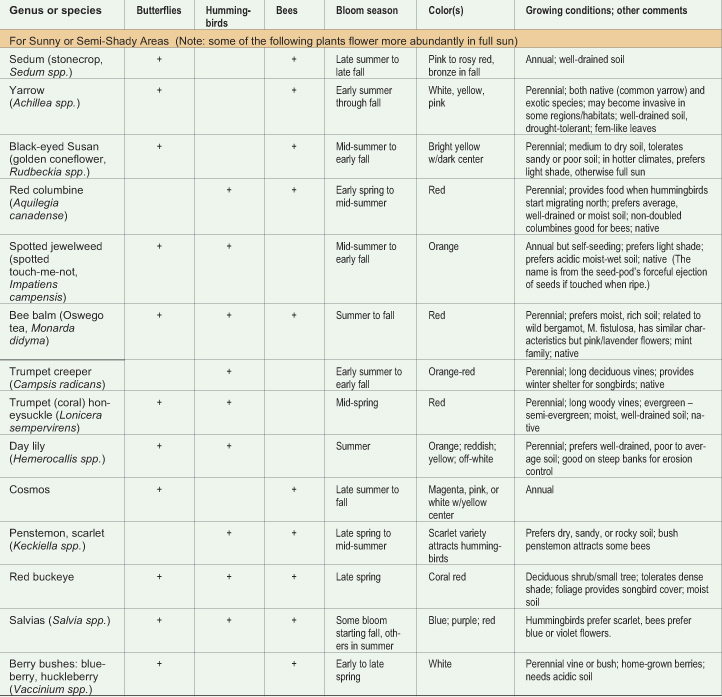

The tables below list annual and perennial plants that attract butterflies and/or hummingbirds and/or bees, but don’t forget that the flowers of trees and shrubs also provide nectar for these pollinators, as well as nuts and berries for many other birds and mammals. For example, spicebush (Lindera benzoin, whose leaves produce a delightful but delicate scent when crushed), sumac (Rhus species) and viburnums (Viburnum species) provide nectar for adult butterflies and bees as well as leaves for butterfly and moth caterpillars.

The National Academy of Sciences is documenting the status of pollinators in North America, to recommend actions to reverse their decline. In addition, a number of groups worldwide, including the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC), are working to conserve pollinators and their habitats and to educate the public about them.

If you’re committed to maintaining a habitat for pollinators and other wildlife, you can apply for wildlife habitat certification (and the associated bragging rights) through the National Wildlife Foundation. Even planting a small area of pollinator-friendly plants may provide critical refueling for some migrating butterfly or bird, or a hard-working bee, so plant and then sit back and enjoy.

The butterflies and other wildlife are now frequenting our yard, and I’m consciously adding perennials and other elements to my garden that will sustain the pollinators that bring so much pleasure to our eyes (and organic produce to our table), a mutualism I expect to continue through the years.

Learn More

Butterfly Gardens: Luring Nature’s Loveliest Pollinators to Your Yard by Alcinda Lewis, editor (Brooklyn Botanic Garden Publications, 2006)

Butterfly Gardening: Creating Summer Magic in Your Garden by The Xerces Society & Smithsonian Institution (Sierra Club Books, 1998)

Author Robin Eisman was a volunteer with the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) when she wrote this article in 2006. Visit their website at http://www.nappc.org.

|