|

Quayside Cohousing:

Creating An Environmentally Sustainable Lifestyle

By Graham Meltzer

Pollsters say that about 90 percent of us claim to be concerned about the state of the environment. And most of us appear to recognize that high levels of personal consumption contribute decisively to environmental degradation. Yet very few of us can claim to have modified our lifestyles accordingly. Why do most of us have such trouble walking our environmental talk? Author Graham Meltzer provides some answers to that question, as well as examples of how things can be different. In his book Sustainable Community – Learning from the Cohousing Model, Meltzer portrays a cohousing project in Vancouver, British Columbia that is empowering its residents to live more sustainably.

"The goal of Quayside Village is to have a community which is diverse in age, background and family type that offers a safe, friendly, living environment which is affordable, accessible and environmentally conscious. The emphasis is on quality of life including the nurture of children, youth and elders." ~Community mission statement

QuaysideVillage Cohousing is characterized by its diversity. True to its mission statement (above) it enjoys a population of diverse age, income, ethnicity, spiritual orientation and life stage. Indeed, its founding members pro-actively sought single, elderly and disadvantaged residents – those often isolated members of society who most benefit from close community ties.

The children have been amongst the biggest beneficiaries. Of the six children under six, four are without siblings, but as a “tribe,” they enjoy close sibling-like relationships. In order to include lower-income households, the project incorporated five “affordable” units (a quarter of the total number), four for sale at 80 percent of market value and one rental unit. The group received no government subsidy for these units, but to improve their viability, the City permitted an increased site density, reduced setbacks and fewer car parks.

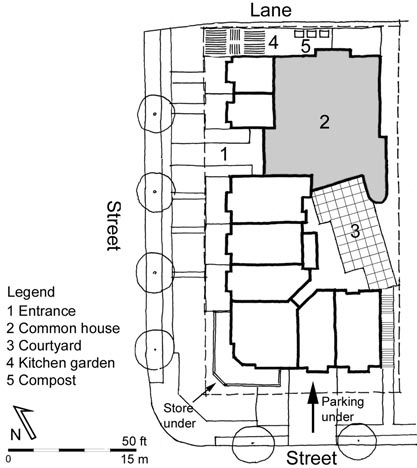

The project is located in the resurgent inner city neighbourhood of Lonsdale, North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. It is 15 minutes from downtown Vancouver by ferry and an easy walk to the ocean, shops, schools, libraries, restaurants and community services. The building is situated on a corner, flanked to the east by similarly scaled four-storey apartment buildings and to the west, by detached houses and duplexes. The somewhat jaunty architecture is richly detailed and brightly painted in “brick dust”, “old linen” and “tea leaf” colours. Individually expressed two and three-storey townhouses face the street, above which two levels of single-storey apartments appear to huddle under a massive gabled roof.

A pre-existing corner store, the Dome Mart, has been resurrected in the new building and its landmark copper dome reinstated above the corner. The units are accessed from generous balconies facing into an intimately scaled, internal courtyard. These offer opportunities for gardening and informal social interaction. Balustrades support the vertical landscaping of creepers and edible plants that provide food, shade and privacy. The common house at Quayside Village is directly accessible from the street and the internal courtyard. Unconventionally, the entrance and principal social space are combined, creating an open and welcoming arrival experience.

A fireplace centrally located within the space incorporates “memory boxes” for display and a round timber bench for seating. Through recycled French doors is a generous multi-purpose space used for common meals, meetings, dancing, yoga etc. It is occasionally let for activities of the broader community, such as a health and parenting program for immigrants. A kitchen, office, guest room, bathroom, laundry and children’s room adjoin. On an upper level, an octagonal domed reading room with stunning city and mountain views is available for reading, homework, craft and meditation.

In accordance with its mission statement, the group has incorporated many environmental strategies and technologies into the project. Most importantly, it is urban and dense. In this way, it uses valuable land efficiently and enables residents to work, live and play in their locality. Six residents don’t own vehicles, preferring to walk, bike and use public transport. The project has been designed to water and energy efficiency standards set by the BC Hydro Power Smart and BC Gas Energy Efficiency programs. A single water meter is deemed sufficient for the whole community. Their grey water recycling plant costing $230,000 was the first in Canada to be incorporated in a multiple housing project. Flooring, leadlight windows and doors were recycled from pre-existing dwellings on the site. One hundred and sixty cubic yards of construction waste were voluntarily sorted by members and delivered to various local recycling facilities. For all of these measures and more, the project won a 1999 Silver Georgie Award from the Canadian Home Builders Association, selected from 444 entries.

If green technology is the hardware, then the software of sustainability is also much in evidence at Quayside Village. Common meals held twice weekly are mostly vegetarian. In summer, they incorporate fresh organic vegetables from the garden. Organic milk and other produce are delivered to residents keen to take advantage of the economy of scale available in cohousing. The waste recycling program is amongst the most effective in cohousing, with potential to reclaim 90 percent of household waste. Tools and equipment are readily shared. Computers and printers move around the building. Kitchenware and garden tools have all been donated to the community by individual households. Two households together own a car while others share their vehicles informally. Only one (disabled) member has a washing machine despite all the units being plumbed for the purpose. Clothes are passed down the line as children outgrow them…and passed on by expanding adults to those a size smaller. The community has its own on-site, licensed childcare centre. All furniture and toys in the centre have come from thrift shops, garage sales or donations.

Many of these outcomes have been instigated by individual, environmentally conscious residents who, in the process, have informed and mentored others. Carol, one of the retired residents, has scoured thrift shops for hand-towels for the childcare centre, and in the process acquired toys, furniture and clothing. Brian, said by one resident to be “a walking model of environmental practice,” administers the recycling program. He collected unwanted bins from all over town for the recycling station and circulated a plan of the ideal under-sink layout to each household. A resident mechanic and computer expert willingly donate their time and expertise, enabling others to maintain and optimize their equipment. One grateful member suggests that, “for people who are interested in environmental practices but without the knowledge or practical skills, the impetus and the motivation and the people to encourage you on, is definitely there.”

Quayside Village offers, in accordance with its vision statement, considerable practical and social support for disadvantaged members. The building is fully accessible by wheelchair and the common areas and rental unit have additional universal design features. The group deliberately sought to include members with special needs and, as a result, two intellectually challenged single men have purchased two of the affordable units. However, their integration into community life has not been easy. The group had difficulty communicating with their parents who, in advocating for offspring, were perceived by some to be interfering in community decision-making.

This is, perhaps, symptomatic of a more general malaise. Vexed communication and poor social cohesion have been worrisome from the outset. One resident explains: “The difficulties and divisions we have experienced are mostly due to people’s knowledge and expectations upon moving in, that is, what they understood living in community to mean or be like. We are struggling with a philosophy of unanimity versus individual needs and expectations”. In part this may be due to literature glowingly advocating for the project during its development phase, in suggesting that:

“By going through the planning, design and decision-making processes together, residents form the bonds which are the basis for ongoing community. Decision-making and responsibilities are shared by all members and decisions are made using consensus. This puts all members on an equal footing, avoids power struggles, encourages everyone to participate by communicating openly and ensures that all aspects of an issue are considered. Any fears about differences that arise as a result of diversity are alleviated through effective communication.”

This is an idealized view of the cohousing development process. A more realistic expectation is put by one of the now much wiser residents:

“North Americans that are moulded by an individualistic and private property model have a very romantic conception of community based on an idealisation of harmony. The idea that a functional community is one that doesn’t have conflict is pure illusion. Conflict is not a sign that a community is not working. Conflicts and differences and disputes are always going to exist.”

With the benefit of this hindsight, the group may well have applied more effort to improving their decision-making and conflict resolution procedures. As it was, the enormous challenge of being the developers and project managers left little time and energy for the purpose, as one founder member recounts:

“We had a difficult development process, dealing with the complexities of construction in an efficient and fair way. We had tax arrears to deal with and problems of a legal and financial nature. A preoccupation with business led to a neglect of social communication that lasted for 18 months afterward and has had ongoing social repercussions.”

Indeed, continued financial pressure has placed an unremitting strain on group cohesion. Costly levies have been introduced to cover ongoing maintenance and unanticipated, retroactive repairs. Collective decisions about the distribution of these costs to individuals and families has necessitated outside facilitation. Some of the difficulty has been structural. Initially, for the purposes of the development process, the group was a legally constituted corporation. At move-in, they adopted a conventional Strata Title but did not formalise an alternative “cohousing-based” set of bylaws to deal with day-to-day issues. “We always believed, based on an unspoken understanding, that consensus and face-to-face negotiation would be enough. We had that level of naiveté,” admits one resident. “In the progression from Corporation to Strata Title it’s been difficult to develop a discourse about Strata versus cohousing versus socially cohesive community.”

A particularly divisive clash developed over usage of the internal courtyard, said by some to be “kid dominated.” Reverberant noise quickly became problematic for residents and adjoining neighbours, alike. A protracted conflict resolution process resulted in guidelines limiting noise at certain times. However, this is a complex issue that goes beyond the simple matters of decibels and times of day. It is underpinned by differences of opinion about child socialization and the dissimilar lifestyles of families and elderly or single members.

The design of a cooking roster generated another vexed discussion over demands on members’ time. Like the noise issue, this dispute results, in part, from the community’s diversity. Some residents deal daily with a stressful cocktail of work life, child rearing, domestic responsibility and recreation. One such member comments: “I don’t see friends in Vancouver because it takes all of my social time to be even minimally involved in this place. I underestimated the amount of time involved and over estimated my willingness to give it.” Other members, on the other hand, are retired, have grown children and enjoy a relaxed lifestyle. Their approach is, naturally, quite different. “The more involved I am, the more I get out of community,” suggests one such retiree.

The difficulty experienced with the cooking roster exemplifies the organisational pressures on smaller cohousing groups. Quayside Village Cohousing has established 13 committees to deal with the day-to-day management of the project: Administration and Finance, Community Building, Building Systems, Maintenance, Landscaping, Parents, Indoor maintenance, Room Rental, Unit Rental, Parking, Safety and Emergency, Recycling, Building Restoration. On average, each committee comprises three members. Therefore, 26 residents (some of whom are inactive) are required to fill 39 positions so most have to sit on at least two committees. Because most members have very busy lives, committees sometimes eschew scheduled meetings. This can be frustrating for others, given that anyone interested in a particular issue may participate in committee decision-making if they so wish. “They make decisions on the fly, in the elevator,” suggests one resident. “Nobody knows where the lines of authority really are.” If the experience of other cohousing groups is any indication, Quayside Village Cohousing will rationalize and fine-tune – if not completely overhaul – its management structure in the years ahead.

The diversity that Quayside Village deliberately sought is probably its biggest challenge, but it is also its greatest blessing. Age diversity, for example, is much valued. Children roam freely throughout the building, visiting a selection of surrogate grandparents. The elderly, who mostly live alone, treasure the contact in return. “I never imagined how much I would enjoy the children,” comments one. “It’s been way beyond my highest expectation.” Ethnic diversity is valued for the opportunity it offers to participate in, and learn about, non-Western traditions. Abi, a Nepalese member, annually adorns the common areas with candles for the festival of Tihar. Jews help celebrate Christmas, and Christians enjoy Hanukah.

Collectively, the group celebrates birthdays, plays music and organizes creative opportunities (such as a mask making workshop said by one resident to be profoundly moving and growthful). Some members encourage each other in fitness work; going to the gym together and having a yoga instructor visit once a week. The group collectively walk their dogs and organize occasional outings. The prospects are bright for this ambitious group. Their high level of commitment to each other and the project is almost certainly going to prevail over their early teething problems. This is generally the experience of other longer-lived groups whose history has been similar.

Postscript

The above excerpt is based on events which occurred in the two or three years after move-in in 1998. Jumping ahead now to some five years on and we find a completely different scenario. “Things are great at Quayside,” says one very satisfied resident. We were just laughing the other night about the weird things that happened [back then] that were so awful at the time and now seem so long ago. Now I feel we've really built a solid and positive community culture − that will continue whatever future challenges may come up.”

The resident continued, “And we have finally established a sort of self-running management structure that has allowed us to decentralize duties more and avoid the ‘too many cooks’ problem of dealing with everything in big and long meetings. At last we have systems in place so a lot of the administrative work is more straightforward.”

In addition to achieving a smoother management system, the community is finding more time and energy for improvements to the building and gardens. “Last year we won two garden awards and this year we are going to be the first ever multi-family dwelling on the North Shore garden tour. We have also had funds to upgrade the interior of the common house.” Their recycling system, as good as it always was, has also improved. “We have reduced our garbage output even more. We are producing between two and four cans per week − less than most single family homes here!”

It appears that a natural process of “community maturation” has occurred at Quayside, whereby members learn to live together more harmoniously over time, develop better group process skills and deepen their understanding of each other's different needs and wants. A natural selection process has also occurred. Members who do not integrate into community life leave and are replaced by others more attracted to the community's values and practices. The Quayside example should hearten and encourage other communities who might be experiencing similar kinds of challenges in their initial few years.

Dr. Graham Meltzer is the author of the book Sustainable Community: Learning from the Cohousing Model (Trafford Publishing, 2005), from which this article was excerpted, with permission, in 2005. He is a leading expert on cohousing. He is an architect, scholar and architectural photographer who consults, researches and lectures in environmental and social architecture, communal housing, and communalism.

|