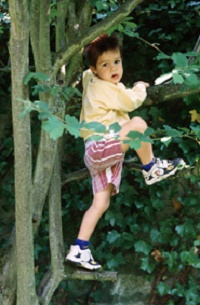

Restless? Go Climb a Tree -

Medicating Children for Being Children

by Wendy Priesnitz

Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat; often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected; often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate; often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly; is often “on the go”; often talks excessively. Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat; often leaves seat in classroom or in other situations in which remaining seated is expected; often runs about or climbs excessively in situations in which it is inappropriate; often has difficulty playing or engaging in leisure activities quietly; is often “on the go”; often talks excessively.

Sound like the kids you know? Then those kids “must” be mentally ill, because that is the definition of hyperactivity found in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). If you read it closely, the definition is laden with words that are judgmental, or at least reflect an adult’s – often a teacher’s – preference for quiet and order. And, although hyperactivity and its ilk are referred to as “learning disabilities,” these characteristics seem not really to get in the way of true learning. Rather, they might describe the normally active, curious child!

By some estimates, the number of American children diagnosed with hyperactivity and other “problems” such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is upwards of five million. In 2013, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) said that 11 percent of American children of school age had been diagnosed with ADHD, which amounts to 6.4 million children. That was a 42 percent increase since 2003. Boys are disagnosed at twice the rate of girls

Some doctors and parents have found that many of the behaviors falling under the Psychiatric Association’s various definitions of childhood mental disorders can be caused by allergies to certain foods, food additives or environmental factors, or by poor nutrition. Studies and clinical trials conducted at Purdue University in the U.S. and Surrey and Oxford in the U.K. indicate that ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia (Clumsy Child Syndrome) may have a nutritional basis.

However, the pharmaceutical industry, which manufactures stimulants like Ritalin, Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse, and Concerta to medicate these so-called illnesses, has a vested interest in helping doctors diagnose and treat them. ADHD drugs are a worth more than ten billion dollars anually to manufacturers. Their marketing is powerful, and an estimated two-thirds of kids diagnosed with ADHD are prescribed drugs to control their supposed problem.

A survey conducted by the Harris polling company for Eli Lilly and Company found that parents report their children have ADHD “symptoms” around the clock but physicians only treat many of their patients for symptoms during school hours. So the push is apparently on to educate doctors about parents’ “need” for further drugging of their children. “Managing ADHD during school is important, but we cannot overlook that managing ADHD during family time plays a critical role as well,” said Richard W. Geller, M.D. of Norwich Pediatric Group, Norwich, Conn., and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, commenting on the survey results.

Fortunately, an increasing number of doctors and researchers would disagree with Dr. Geller and, using a more nuanced approach, have been coming out against the acroos-the-board psychopharmaceutical approach to the behavioral management of children, i.e. redefining normal but inconvenient childhood behavior as a mental disorder.

Priscilla Alderson, Professor of Childhood Studies at London University, told The Times newspaper quite plainly that legitimate syndromes such as attention deficit disorder was being exploited by psychologists keen to make a quick buck. Some life learning parents would agree with her; there is a great deal of anecdotal evidence that when diagnosed kids leave school, its environment, and behavioral expectations for home-based learning their “symptoms” disappear. Other families find that some children’s and attention span improves with dietary changes.

Fred A. Baughman Jr., MD has been an adult and child neurologist, in private practice, for over 40 years. He views the “epidemic” of ADHD. with increasing alarm. Dr. Baughman describes it this way, “[Psychiatry] made a list of the most common symptoms of emotional discomfiture of children; those which bother teachers and parents most, and in a stroke that could not be more devoid of science or Hippocratic motive, termed them a ‘disease.’ Twenty five years of research, not deserving of the term ‘research,’ has failed to validate ADD/ADHD as a disease.”

In addition to scientific articles that have appeared in leading national and international medical journals, Dr. Baughman has testified for victimized parents and children in ADHD/Ritalin legal cases, writes for the print media and appears on talk radio shows, always making the point that ADHD is a creation of what he calls the “psychiatric-pharmaceutical cartel,” without which they would have little reason to prescribe its drugs.

Ned Hallowell, a psychiatrist and author of the books Driven to Distraction and Delivered from Distraction, says, simply, “We are pathologizing boyhood.” (He, by the way, is pro-medication for those who really need it to deal with a real problem.)

There is also evidence that some ADHD-type behavior is a result of the demands of school not being in synch with the behavioral stages of young boys. A huge 2012 study, entitled “Influence of Relative Age on Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children” and published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, looked at one million children between the ages of six and 12. The results reflected a pattern set up by kindergarten enrollment procedures, which allow children to enroll in kindergarten in September if they turn five by the end of that calendar year; those turning five in January and beyond must wait until the following September. The researchers found that boys who were born in December (and therefore the youngest students in their class) were 30 percent more likely to receive a diagnosis of ADHD, and 41 percent more likely to be medicated, than boys born in January, who were a full year older.

While ADHD is a valid diagnosis, it has been watered down to include children who are just immature or developmentally different from what is required by the sit-down-and-listen style of classroom education. Dr. Allen Frances, professor emeritus at Duke University School of Medicine, says that the ADHD diagnosis has become so common that it is meaningless. It is now “a disease called childhood,” he says.

Ultimately, whether or not to accept a diagnosis of ADHD and then whether or not to fill a prescription for a drug to manage that behavior, is up to individual parents. There are many questions to be asked. For instance: Can the behavior in question be seen as a benefit rather than a deficit? (Check out the work of Howard Glasser, and his book Transforming the Difficult Child.) Are the side effects of the stimulants acceptable? Is it necessary for any particular family to have their child behave in the way a given school requires?

Lucky are those whose parents can help them avoid the behavioral demands of the classroom by facilitating life learning!

Wendy Priesnitz is the founder and editor of Life Learning Magazine, a well known home-based learning advocate since the 1970s, the mother of two adult daughters who learned without school, and the author of 13 books. This article was published in 2004 and updated in 2019.

Copyright © Life Media

Privacy Policy

|